Never Retire Gets Real: Peanut Butter Economics and the True Cost of Living

Six months into our life in Spain, Never Retire is shifting gears—less wanderlust, more real talk about how we spend, work, and live without burning out.

The Never Retire newsletter helps people in and around midlife organize their money, work, and lifestyle so they can slow down on their own terms—and still thrive in the second half of life.

I turn 50 next month. And I plan to live to 100.

So as I hit this halfway point, it feels like the right time to revisit and recommit to the mission of Never Retire—not just as an idea, but as a structure for how to keep living and working without working too much.

Working less now so you can work less longer.

Over the last several months, as my wife and I moved to Valencia, I’ve mainly used this space to tell stories—about place, culture, people, and what it feels like to settle into a new life.

Never Retire has been more story than strategy, more street life than spreadsheets. That wasn’t a pivot—it was just reality.

That’s what my life has been lately. But Never Retire has always been about more than just where we are. It’s about how we live, and the decisions we make that give us time, space, and freedom—no matter where we are.

But I said I’d get into the more practical aspects of living in Spain after six months here. Not just how they apply to people living abroad or thinking about doing it, but how they apply to the notion of Never Retiring in the first place.

Starting today and going forward—

We’ll talk about the money side, yes, but also about how the rhythms of daily life here change your values, your habits, and how you spend—on purpose or not.

So, consider this the start of a new season. More stories, yes—but with a renewed focus on the how, not just the wow.

Strategic Spending, Big and Small (aka Peanut Butter Economics)

Never Retire is built on being strategic financially as it meets emotionally—not just about the big stuff like taxes or earning structure, but also the little things.

Back in LA, I’d think nothing of a $5 coffee. Why? Because that cup bought me 60 to 90 quiet minutes to decompress, read, and draft ideas. That was a worthwhile return.

As absurd as it was—and is—to pay $5 (and now more for a cappuccino), there was value in the near-daily expense. Add in a $5 pastry and the value remained, because in LA I was buying an experience that did something for me.

Now, in Spain, I will never be able to go back to those toxic economics on what should be treated and priced as a daily staple. It was mentally anguishing enough to have to do it for two weeks in San Francisco last month.

But my perspective has changed. The latte effect will always be one of personal finance’s dumbest concepts. It’s just that Spain has permanently adjusted my threshold on price as it meets a much better day-to-day bar and cafe experience.

That said—

Here in Valencia €7.35 jar of peanut butter or an €7.29 pint of ice cream?

There’s no payoff. It’s not strategic. It’s not joyful. At least not for me—a self-proclaimed peanut butter lover, who—turns out—doesn’t love peanut butter (or ice cream) as much as he thought he did.

However, peanut butter or ice cream (or whatever) might remain your thing. Maybe it has gone up in price wherever you live these last few years and you still buy it. Maybe you cut back on other items that—turns out—you don’t want or need as much as you thought you did.

As much as it sucks to pay a premium—often due to nefarious macro and microeconomic reasons out of our control—there’s nothing wrong with splurges that have positive psychological effects that might actually save us money in the bigger picture.

You can still pay less for American ketchup in Spain than you do in America.

How Street Life Redefines Spending

You don’t have to buy your way into social life in Spain.

You just show up. The plazas, benches, cafes, and markets do the rest.

People shop small—literally. Small bags, smaller daily hauls. You eat what you buy that day for a day, maybe a few. That keeps costs down and waste low. We have seen the difference on both counts.

It doesn’t appear that people here are budgeting harder than they do any place else—it’s that the system encourages less waste, more walking, and a rhythm that’s slower and more grounded by default.

There’s something wrong with a society where coffee in a cafe or beer in a bar becomes inaccessible to large swaths of the population. When one person blows off dropping $5 a day on a coffee and somebody else can’t justify or is literally unable to make the purchase on anything resembling a regular basis.

Thanks, Starbucks for your bullshit coopting of the Third Place and making $5-plus coffee the apathetically-accepted standard, if not an aspirational status symbol in the United States.

The Real ROI on Living Here

On paper, we are saving money. But we’re not suddenly rich!

But we are getting more for what we spend—and often, more for what we don’t.

Not in the “my dollar goes further” sense. I don’t like that attitude. It’s not like we’re buying five things for the price of two and stuffing the fridge just because we can.

We still buy what we need—two or three things, not five. We’re just not constantly fighting a system that pushes you to overspend for the basics of daily life.

Grocery stores don’t do huge discounts, if they do discounts at all.

It’s in the experience:

A stress-free Saturday that doesn’t cost €150. In LA, if you decided to have a day out—from morning until night—you could not do it for less than $150, minimum. That’s a shame.

Errands by foot, not by car.

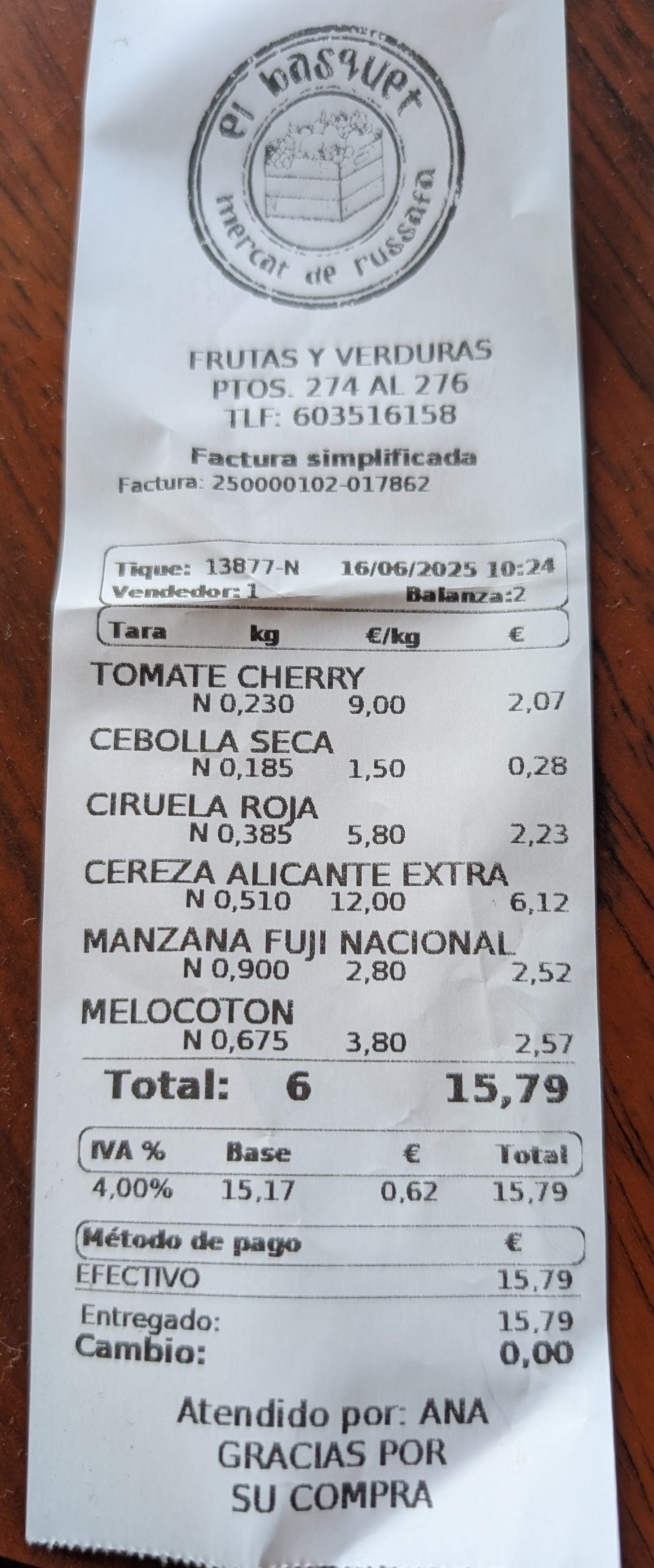

Cherries in season that you actually buy instead of skip. See the receipt below for proof that you can buy fresh local and regional produce without feeling like you got fleeced.

Eggs, meat, nuts, dried fruit, and olives from the market. Good stuff that would’ve felt like splurges back in L.A.

$4 bottles of wine that drink like $15.

Just over a pound of (incredible) cherries for 6€. Not even possible in many U.S. supermarkets. Same goes for just about everything else on the list.

And it’s not for the reason many Americans love to push: Well, we make more money than “they” do there. That’s an inferiority complex disguised as superiority.

The reality is more complex—and frankly, more interesting. It has to do with how food is grown, distributed, sold, and valued in a country that seems to care more about the well-being of its citizens than about squeezing every last euro out of their grocery budgets.

It’s something I plan to dig into more deeply. But even just living with it day to day, you feel the difference.

The point isn’t that we’re balling out on a budget. It’s that life outside your house doesn’t feel cost-prohibitive. The streets, the markets, the bars—they’re part of life, not luxury. And that changes your habits without you even realizing it.

To be clear: none of this just happened.

We planned. We adjusted. We built this lifestyle. We still work. We still track income and expenses. But we finally get to live the kind of life we were trying to carve out all along—just without the constant pushback and quality of life degradation American cities sadly provide.

So yeah—Spain is affordable. But the real win isn’t just what things cost. It’s how spending aligns with living.

Next time, I’ll write about what work looks like now—what I’ve kept, what I’ve dropped, how I make money without burning out, and what I consider “enough” at this point in life.

I love this idea that if you shop more frequently and in smaller quantities, then waste is lower.

We have been able to change our habits from doing a huge weekly shop for four, with two kids now out of the house we simply buy what we need when we need it. I have the time to take care of that.

Time is definitely a factor, so I can understand that people still buy in large qualities need them have deliveries or do a single big shop in a large supermarket

Lately I've become painfully aware of how much plastic comes in and out of the house. I'm trying hard to cut down even thought I feel overwhelmed by the problem. ( and my efforts gravely insignificant ) What does it feel like in Spain? And what is the attitude over there about the problem.